Press

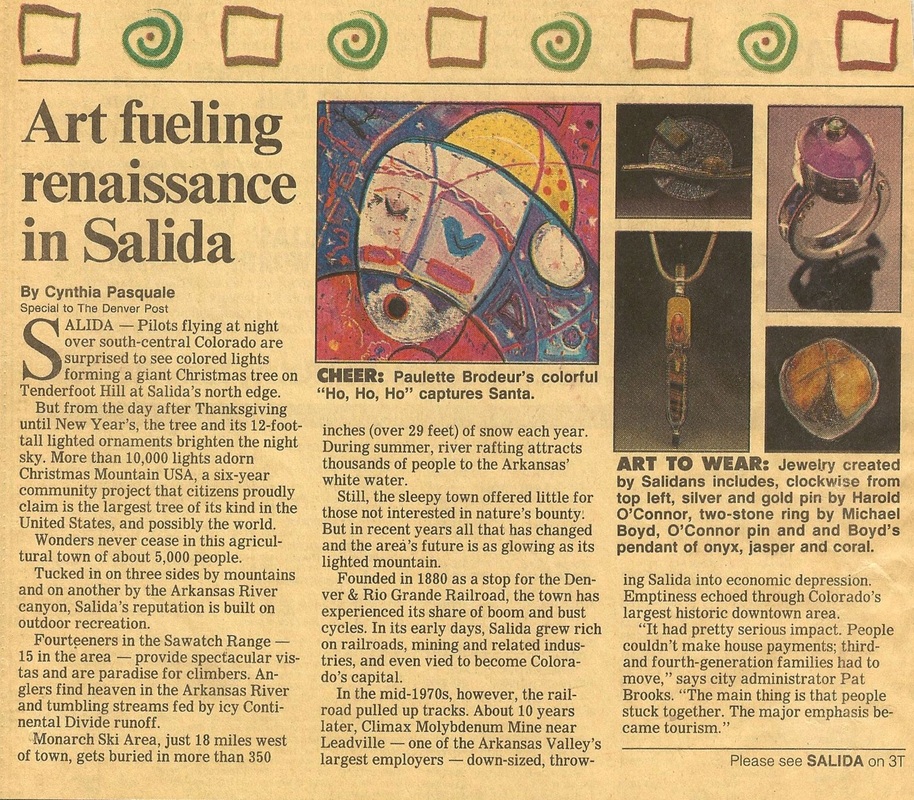

THE DENVER POST Sunday December 18, 1994

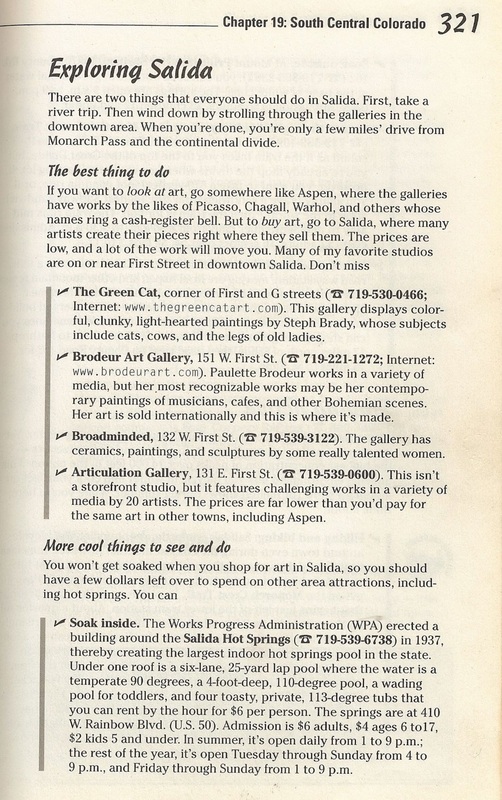

FROMMERS 2003

An unspoiled slice of Colorado - In laid-back Salida there's more than great whitewater

By Diane Daniel, Globe Correspondent | June 28, 2006

SALIDA, Colo. -- The threats came in before I even arrived in Denver.

``Tell her to bury that story," advised a colleague of the friend I was planning to visit in the Mile High City and take along on a weekend getaway 145 miles to the southwest. When I met said colleague, the first words out of his mouth, only half-jokingly, were, ``I'm part of that group asking you not to write about Salida." Wow, I hadn't known there was an entire posse trying to keep a lid on things. Perhaps they'd missed Outside magazine's declaration two years ago that Salida is an ``American Dream Town." So let it be known that I am not the spoiler, or at least not the only one.

It is true, though, that there are still a good number of people who have never heard of Salida (pronounced suh-LIE-duh). Even many Coloradans pass by without stopping, though the town is only a short detour from the highway. They don't know what they're missing.

The whitewater folks, however, are in the know. In the summer , when the Arkansas River is racing, more than a dozen rafting and kayaking operators spring to life in Chaffee County . And every June, about 10,000 visitors triple Salida's population for the Blue Paddle FIBArk Whitewater Festival (``FIBArk" stands for First in Boating on the Arkansas River) . Arguably the country's top whitewater event, the fest draws the sport's stars, who come to race and trick out on the rushing waters. Depending on when you visit, you can experience rapids from a nothing Class I to a menacing Class V. Salida is but one of the stops along the Arkansas Headwaters Recreation Area , a 148-mile linear park of riverbanks and river.

Whitewater is center stage in the city-run kayakers' ``play park," officially the Arkansas River Whitewater Park and Greenway , where from bleachers set up for spectators you can watch those maniacs play in the rapids, roll upside-down over and over, and get water up their noses. (You can't tell me those plugs really work.)

Luckily one doesn't have to be a paddler to enjoy Salida's riches. My friend and I, who get white-knuckled even thinking about whitewater, merrily eliminated going down the stream. Instead, we cycled, strolled, shopped, dined, and generally made ourselves at home in this incredibly congenial town. We discovered that the abundance of friendly folks wasn't a show for the sake of commerce. Even the locals talk about how friendly the locals are, and many compare unpretentious Salida with snootier Colorado towns.

``In Aspen and Vail people want you to know they know everyone and have been everywhere. Here, you just know they have, but they don't need to tell you," said Jeff Schweitzer, who with his chef wife, Margie Sohl , owns Laughing Ladies Restaurant , arguably the best dining in town. The night we ate in the small, cheery establishment, Schweitzer toured the room several times, chatting with diners he knew, which seemed to be half the room, while passersby would wave from the sidewalk to friends inside.

Modern-day Salida plays up its appeal to tourists and relocating retirees, but back in the 1880s, the city boomed for being top post on the main line of the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad . The railroad left in 1950, but mining kept things going until the bust in the 1980s. Despite the recent influx of tourists and new residents, ranching and agriculture remain a mainstay. Signs of both worlds are charmingly evident on downtown streets, as old pickup trucks with ranch mutts barking from the back pass by SUVs sporting shiny bicycles and brightly colored kayaks on their roof racks.

The compact downtown is wonderfully down to earth, not yet having fallen victim to chain stores and developers. Virtually every building in the historic section is more than 100 years old and made of red brick, thanks to a town code that was enacted after fires in the late 1880s destroyed much of the city. We looked out for Victorian homes along side streets, and looked up inside every building we entered. Yep, we'd nod, another gorgeous tin ceiling.

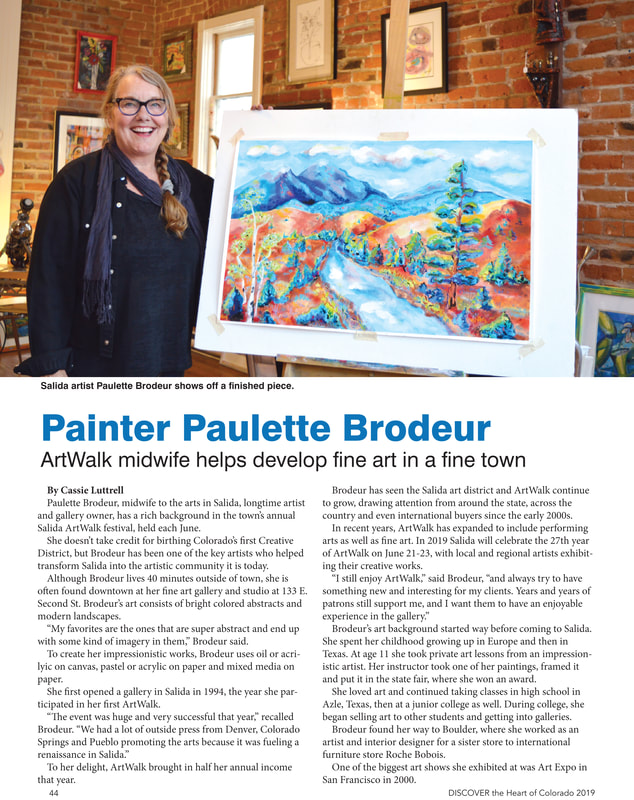

Salida is building a reputation for its artwork as much as for its outdoor play. Monthly receptions (second Saturdays) have brought the dozen galleries together , and a large three-day art festival among the shops has been held in June for the past 14 years. We were particularly fond of Culture Clash for its mix of works from regional artisans, The Bungled Jungle for its menagerie of crazy creatures, and Brodeur Art Gallery for its amazing mix of media all from one font of creativity, Paulette Brodeur. She had a great show up called ``Adventures in Salida," or, as she put it, ``what makes Salida Salida," with contemporary impressionist paintings of cyclists, kayakers, mountains, and more. Brodeur also decorates lampshades, makes jewelry, and paints funky pet portraits. She even turned her father's old bomber jacket and her mother's dilapidated fringe coat into sculptures.

``When I moved here 12 years ago Salida was a ghost town," said Brodeur, who lives a ways east in rural Cotopaxi. ``There wasn't even a coffee shop. The growth has been gradual. I think this is going to be the year. I love being here and meeting all the people. But when it tips to what I don't like, I'm outta here."

If this isn't ``the year" for Salida, it could be 2009, the projected time for environmental artists Christo and Jeanne Claude's next installation. The pair have a project in the works to hang dancing fabric over eight segments of the Arkansas River, for a total of 7 miles between Canon City and Salida. It's still in the approval process, but, if it happens, the two-week exhibit is estimated to attract some 250,000 visitors.

But, as that posse from Denver would say, don't tell anyone.

Contact Diane Daniel at [email protected].

5280 - Rocky Mountain Renaissance - Salida Colorado July 2005

As we approach Salida, the sun is low in the sky above the Collegiate Peaks. Mt. Yale and Mt. Princeton-Tim and I ponder this nod to East Coast academia. Will they ever name a peak after CU (our alma mater)? We decide not. Definitely not.

It's been three hours since we left Denver, and we've already exhausted the iPod battery. Tim starts flipping though the radio stations. Country, bluegrass, more country. I crack a bottle of root beer and kick my feet up on the dash. Ever since we made it over Kenosha Pass and into Park County, we've gone into chill mode. We can't help it-the landscape dictates it.

It's one of those perfect Colorado sunsets, when the clouds catch the pink and orange hues of light and seem to hold onto them just a little bit longer than usual. The River Run Inn, our abode for the next two days and nights, sits on a wide bend of the Arkansas River. Before we even check in, we head down the path to the banks of the river. And as we walk along the gin-clear waters to take in the colors, we wish we had packed our fly rods.

But there are no fishing poles on this trip, no mountain bikes, and no kayaks. I didn't even bring my hiking boots. Here we are, in what Outside magazine last year touted as one of 'America's Dream Towns," but we aren't planning to spend much time in the great outdoors. We've come to Salida with a different mission: We've come to see the art.

Our gear for the trip: an advance copy of the 2005 Salida Art Walk map, walking shoes, and two French berets (mine is raspberry). All right, so there are no berets. But next time I go to Salida, I'm bringing one. And I'm taking a velvet, lime-green shawl, which I'll swoop dramatically over my left shoulder as I ask,"What was your inspiration for this piece?"

It's been three hours since we left Denver, and we've already exhausted the iPod battery. Tim starts flipping though the radio stations. Country, bluegrass, more country. I crack a bottle of root beer and kick my feet up on the dash. Ever since we made it over Kenosha Pass and into Park County, we've gone into chill mode. We can't help it-the landscape dictates it.

It's one of those perfect Colorado sunsets, when the clouds catch the pink and orange hues of light and seem to hold onto them just a little bit longer than usual. The River Run Inn, our abode for the next two days and nights, sits on a wide bend of the Arkansas River. Before we even check in, we head down the path to the banks of the river. And as we walk along the gin-clear waters to take in the colors, we wish we had packed our fly rods.

But there are no fishing poles on this trip, no mountain bikes, and no kayaks. I didn't even bring my hiking boots. Here we are, in what Outside magazine last year touted as one of 'America's Dream Towns," but we aren't planning to spend much time in the great outdoors. We've come to Salida with a different mission: We've come to see the art.

Our gear for the trip: an advance copy of the 2005 Salida Art Walk map, walking shoes, and two French berets (mine is raspberry). All right, so there are no berets. But next time I go to Salida, I'm bringing one. And I'm taking a velvet, lime-green shawl, which I'll swoop dramatically over my left shoulder as I ask,"What was your inspiration for this piece?"

"It was totally deadsville," says Paulette Brodeur of the Salida she found when she first arrived in 1994. "It was a ghost town. But rent was next to nothing, and working here sure beat working at WalMart." Brodeur is one of the original Salida artists-a handful of funky folks who, over the past 10 years, descended on this sleepy mountain hamlet looking for inspirational views and cheap rent, and ended up turning the whole town around. Brodeur came here from Boulder. Others came from Denver, New York, Kansas, and elsewhere. "It just sort of grew naturally" she says.

Today Salida's once-boarded storefronts are painted lively colors to match the artwork and artisans they house. Gourmet restaurants, cozy coffee shops, and yuppie yoga studios take the place of Old West saloons and brothels (you can imagine how Laughing Ladies, Salida's critically acclaimed eatery, got its name). And yes. There is art-every- where. Even the local Laundromat doubles as a gallery. We start our day at Bongo Billy's Salida Cafe-a former feed shop- which is nestled between a bicycle store and the community sculpture garden. As we sip our coffee on the back porch, we watch boaters maneuver a kayak course in the Arkansas. We can tell right away that, while it does have art, Salida is no Santa Fe. A baby in the realm of art towns, it's still finding its personality.

But that's what gives the town its charm. You can't quite define the eclectic mix of people that call this town home. The crowd at Billy's this morning: Spandex-clad mountain bikers, grungy raft guides, blue- haired church ladies, and artists with dried paint on their pants. The 13th Annual Salida Art Walk map in hand, we start up F Street and begin visiting the galleries along the route.

Today Salida's once-boarded storefronts are painted lively colors to match the artwork and artisans they house. Gourmet restaurants, cozy coffee shops, and yuppie yoga studios take the place of Old West saloons and brothels (you can imagine how Laughing Ladies, Salida's critically acclaimed eatery, got its name). And yes. There is art-every- where. Even the local Laundromat doubles as a gallery. We start our day at Bongo Billy's Salida Cafe-a former feed shop- which is nestled between a bicycle store and the community sculpture garden. As we sip our coffee on the back porch, we watch boaters maneuver a kayak course in the Arkansas. We can tell right away that, while it does have art, Salida is no Santa Fe. A baby in the realm of art towns, it's still finding its personality.

But that's what gives the town its charm. You can't quite define the eclectic mix of people that call this town home. The crowd at Billy's this morning: Spandex-clad mountain bikers, grungy raft guides, blue- haired church ladies, and artists with dried paint on their pants. The 13th Annual Salida Art Walk map in hand, we start up F Street and begin visiting the galleries along the route.

By the time Tim and I arrive at Brodeur's vibrant gallery (which doubles as her studio), we're ready for a rest, so we flop into two big chairs in the corner. "Look. He lets me pet him," Brodeur says to us as she reaches into a fishbowl to stroke her oversize pet goldfish, Pig. The fish dodges her touch. "Well, he won't let me do it today"

The eccentricities in her personality are contagious, and we end up spending more than an hour chatting as we rest in her comfy chairs. But Brodeur's lovable personality is no match for the whimsical pastels that hang, lean, and pile up in every square foot around us. There's one of a dog dressed in a blue dress and jewelry, smoking a cigarette. This is one of her "pet portraits" popular, she tells us, with her New York patrons.

But Brodeur doesn't just sketch animals. I'm more intrigued by her portraits of humans. There's one abstract depiction of a female nude with flowers resting on the table next to her; her expressive eyes still haunt me today.

Tim and I didn't buy any art on this trip. But we both had favorites that, should we return to Salida, will no doubt make the trip back to Denver with us.

The eccentricities in her personality are contagious, and we end up spending more than an hour chatting as we rest in her comfy chairs. But Brodeur's lovable personality is no match for the whimsical pastels that hang, lean, and pile up in every square foot around us. There's one of a dog dressed in a blue dress and jewelry, smoking a cigarette. This is one of her "pet portraits" popular, she tells us, with her New York patrons.

But Brodeur doesn't just sketch animals. I'm more intrigued by her portraits of humans. There's one abstract depiction of a female nude with flowers resting on the table next to her; her expressive eyes still haunt me today.

Tim and I didn't buy any art on this trip. But we both had favorites that, should we return to Salida, will no doubt make the trip back to Denver with us.

"This place is going to be packed for the Christo thing," Brodeur says to us, obviously trying to disguise excitement with aloofness. We take the bait. What Christo thing?

It turns out that for their next big project, Christo and Jean-Claude - the conceptual artists of New York's recent "The Gates" fame-plan to drape fabric over portions of the Arkansas River, just outside of town.

The "Over the River" project is slated to arrive in Colorado in 2008 (at the earliest, if all the permits clear). Brodeur seems to think "Over the River" will put Salida on the map. I smile just thinking how many raspberry berets will be in Salida when Christo comes to town.

Tim and I pack the truck Sunday morning, both of us silently thinking we'd rather sit by the river than sit in the car. But the open road calls and we're game. As we pull out from the gravel driveway of the River Run inn, we can't help but laugh as we imagine Christo holding a press conference right there on the front porch with Barley, the inn's overzealous dog, jumping at his feet.

CHERYL NEDDERMAN

It turns out that for their next big project, Christo and Jean-Claude - the conceptual artists of New York's recent "The Gates" fame-plan to drape fabric over portions of the Arkansas River, just outside of town.

The "Over the River" project is slated to arrive in Colorado in 2008 (at the earliest, if all the permits clear). Brodeur seems to think "Over the River" will put Salida on the map. I smile just thinking how many raspberry berets will be in Salida when Christo comes to town.

Tim and I pack the truck Sunday morning, both of us silently thinking we'd rather sit by the river than sit in the car. But the open road calls and we're game. As we pull out from the gravel driveway of the River Run inn, we can't help but laugh as we imagine Christo holding a press conference right there on the front porch with Barley, the inn's overzealous dog, jumping at his feet.

CHERYL NEDDERMAN

'It's hard work being a kid'

|

Artist sips, schmoozes

and sells Text and Photos by Denise Ronald Mail Staff Writer ______________________ Painter Paulette Brodeur is frequently seen sitting in front of her Second Street gallery, sipping a glass of wine, talking to passersby, friends and clients. "Many art galleries are stuffy. I like to keep my gallery homey and comfortable, giving my clients a sense of who I am," she said. "So, I like to open a bottle of wine and sit down with people to chat. "I think that is the reason I am as successful as I am. I keep in touch with my clients. Many of them become friends. "I try to send cards, letters, and emails on a regular basis. My husband, Marty, is also helping me with my website. It is a lot of work, but it keeps people coming back." Brodeur said many of her works have been inspired by her clients, as well as music, movies and books. "People send me postcards and tell me stories that get me thinking. I am good at imagining that I am at these places with them. "Once I form a visual image, I start refining it in my mind and eventually it pops out as a piece of art." Music plays a major role in the creation of Brodeur's work. She works with music playing and she said most of her friends are musicians. When she was in high school, Brodeur played alto saxophone and baritone horn in All State Band. "I would love to start playing the sax again, but I just don't have the time. It would be fun to sit in front of the gallery at the end of the day playing music. "People think I sit around and don't do much, but I really do work a lot. I mean, where do people think all of this art comes from?" Brodeur is in what she calls her "acrylic phase" right now and spends most of her time working in that medium. She also creates in oil, ink and airbrush. The Cotopaxi woman said she will paint on anything. If she runs out of canvas, she paints on paper, frames and ceramics. |

Paulette Brodeur stands next to her favorite bicycle while showing off a recently completed painting of a martini in one hand and the inspiration for the painting in the other.

Photo by Denise Ronald When she is not creating a new work of art, Paulette Brodeur enjoys decorating her own frames. The artist said none of her work is ever complete until it is sold. Occasionally, she will repaint a frame or touch up a painting if she decides she needs to change something.

Paulette Brodeur shows off a painting to clients.

|

"I think I would describe my work as whimsical, expressionistic and abstract. Sometimes it's a combination of all of these things."

Whimsical is a good word to describe the artist as well. Brodeur has a child-like interest in everything around her. "I am really a 10-year-old girl trapped in the body of a grown woman. It's hard work being a kid, but that child-like energy is a big part of my creativity," Brodeur said. Like a child, Brodeur said she gets bored easily and oftentimes works on several projects, in different mediums, at once. Originally from El Paso, Texas, Brodeur was the daughter of military parents and spent a good part of her childhood living and traveling throughout Europe. "My dad was a pilot for the Air Force and spent a lot of time flying secret missions. We moved frequently because of that, but I got to experience a lot of the world." Brodeur graduated from high school in Fort Worth, Texas. She went to the Art Institute of Dallas and eventually to Tarrent County Community College in Fort Worth. She quit college to become an interior designer. Although she said she enjoyed the work, her heart wasn't in it. On her 40th birthday, after 18 years in interior design, Brodeur decided to follow her heart and become a full-time artist. "I have been so blessed. I am making a living doing work I truly love. "The best part is that I'm free, I'm myself and I get to create something everyday. "I also enjoy the positive comments I get from people. I am selling a part of myself, my soul, with each piece of work that leaves my studio." Article courtesy of The Mountain Mail newspaper in Salida Colorado. |

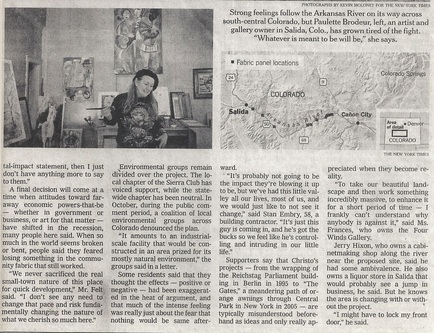

THE NEW YORK TIMES NATIONAL

Friday November 26, 2010

Friday November 26, 2010